Today, March 8 2025, is International Women’s Day. I would love to start this newsletter by proclaiming that there has never been a more necessary time to be a feminist. I can’t do that, because that’s absolutely not true. If it was, I wouldn’t be able to return to sources who wrote for such times as these. I wouldn’t be able to look towards my bookshelf — a space where I collect revolutionary works for me to delve into whenever I choose to. It is as crucial as time as ever, yes, but it doesn’t stand alone.

Instead, I will ask “what am I learning from what I invest in?” I venture here and draw out anything I have on feminism — particularly, Black Feminism.

Black Feminism is the emphasis of the interconnectedness of various forms of oppression, highlighting how race, gender, class, sexuality, and other factors intersect to shape individuals' experiences and identities.

I don’t recall first learning about Black Feminism. Perhaps I am old enough to understand why the older women in my family struggle to dissect particular details of their lives. I do know that over the last decade, I have become increasingly aware of how I shape my political practice to be a Black feminist shaped by Black feminism.

My devotion to this political alignment is my knowledge that Black feminism is a commitment to community. To bind my work to the liberation, autonomy and protection of those most derided in society is to free us all. In their 1977 statement, feminist coalition, The Combahee River Collective, stated:

If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.

I wanted to share books on my shelf that emphasise Black feminist teachings.

Now more than ever, I recommend reading at least one book by a Black feminist writer. We need not endure this world that daily assaults the humanity of womenkind alone. Not when we have a wellspring of writing created for a present, and a future such as this. I collect the works of authors, poets, activists, scholars and revolutionaries to inform the language that I use. I do not waver when I talk about what matters to me, because I know I am a mere echo for the voice of writers and speakers who archived their thinking in the printed word.

When we speak of our power, may we sharpen the edges of our teeth against the sound of our voices to bite into our freedom.

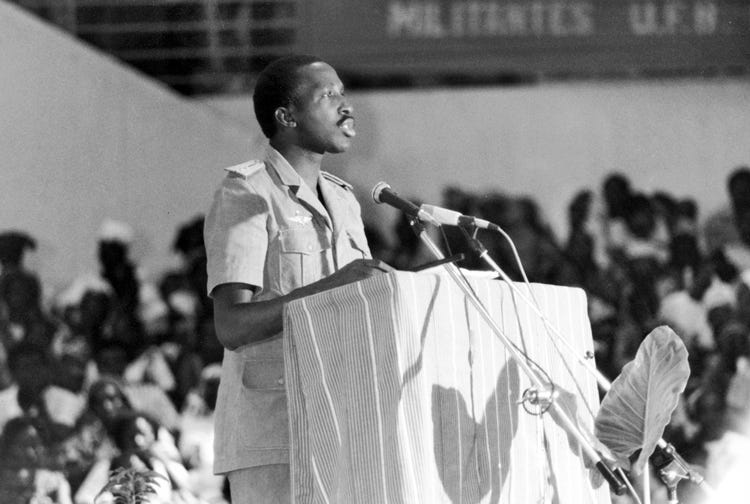

“Women's Liberation and the African Freedom” Struggle By Thomas Sankara (2002)

“May my eyes never see and my feet never take me to a society where half the people are held in silence.”

Thomas Sankara served as Burkina Faso’s president from 1983 until his assassination in 1987. This text is a record of Sankara’s speech to women in Burkina Faso (pictured above) on International Women’s Day 1987. In under 72 pages, Sankara delivers one of the most iconic speeches on gender equity. I cling on to this book because is unbelievably rare to have evidence of a 20th Century freedom fighter who intentionally included the liberation of women, pointing how everyone’s freedom would not be attained without it.

“Your Silence Will Not Protect You” by Audre Lorde (2017)

A posthumous collection of speeches, essays and poems by Audre Lorde. Lorde was also a founding member of the Combahee River Collective. The first time I read this, it took me almost 3 years to finish it — the first time my inner turmoil about this world was read back to me eloquently. Lorde’s writing is influenced by the myriad of identities — being Black, lesbian and a mother. Some of essays contained in “Your Silence” were written in the years following Lorde’s breast cancer diagnosis. An undeniable reminder that Black women are writing for their lives.

“for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf” by Ntozake Shange (1976)

“for colored girls” is as innovative as it is transformative. It is the first choreopoem play — a phrase coined by Ntozake Shange. Debuted in 1976, Shange created poetry focused on the experiences of 7 women marginalised by sexism and racism. When performed, the poems are accompanied with music and dance. Writing that illuminates the dangers women are subjected to, and how poetic language, dripping in sorrow and endurance, can irrupt from this to navigate us forward.

“Part of My Soul Went With Him” by Winnie Mandela (1985)

“Part of my Soul” was published in the final year of Winnie Mandela’s 8-year banishment in the remote town of Brandfort, South Africa. It is a rare account from Ma Winnie during her years of crippling restrictions and constant surveillance by the apartheid government. Despite her self-proclaimed resistance to write an autobiography, this book contains conversations with her, letters speeches and historical notes from her, and from those closest to Ma Winnie. For her graciousness and foresight to share, I am thankful. A necessary read accounted for during the height of South Africa’s liberation struggle, from one of the most crucial figures a part of it’s movement.

“Sisters of the Yam” by bell hooks (1993)

“Just so you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter. A lot of weight when you are well.” - “The Salt Eaters”, Toni Cade Bambara

bell hooks opens with the words of her friend and celebrated writer Toni Cade Bambara. In this work, hooks pens personal essays addressing the well-being of Black women, constantly weighed heavy by institutionalised systems of domination. The first time I learnt how vital it was for me to heal was reading this book. bell hooks wanted us to be well. She wanted us to function and sustain through organised resistance struggles with a wholeness and fullness society does not allow us to attain. hooks left us with vital teachings on healing for a communal and personal purpose.

“Sturdy Black Bridges: Visions of Black Women in Literature” edited by Roseann P. Bell, Bettye J. Parker, Beverly Guy-Sheftall (1979)

This anthology is a collection of essay, interviews, poems and stories focused on how literature characterises Black women from the United States, the African continent and the Caribbean. The collected writings in it gather Black women writers with a myriad of experiences, renown and perspectives. I admire how Black writers have always understood the vitality of seeing ourselves in the future. Today, I write and live in the era these writers created. My world and bookshelf are enlargened knowing this book.

“Feminism Interrupted: Disrupting Power” by Lola Olufemi (2020)

Lola Olufemi is a modern voice amidst the 20th century works above. In writing this, Olufemi sought to reclaim the commodification of feminism today. This book tackles a myriad of socio-political and economic areas and peers through them with a feminist lens. It is a radical vision into the future Olufemi and the feminists that brought her here conjure — in words, in inspiring readers, in directing her audience to likeminded thinkers.

This is an in-exhaustive list that is ever-growing and limited by my perspectives, still budding and curious. I welcome you to comment any that you want more people to know.

For Women’s History Month, I will be MC-ing Woman Scream — a free annual event in Boorloo/perth for poetry, performance, and community hosted by author and poet, Manveen Kaur Kohli. You can RSVP here, and you RSVP.

Women Scream is partnering with and fundraising for Starick Domestic Violence Support Services. Please consider providing a donation here.

Thank you so much for sharing!

I look forward to seeing this list grows for you👏🏿